Intro: your body’s thermostat is throwing a party (and you’re invited, unwillingly)

It’s 3 a.m., your forehead feels like a pocket heater and you’re alternating between sweating like a marathoner and shivering like a cartoon villain. Welcome to the fever experience: uncomfortable, dramatic and oddly useful. Fevers are an ancient biological trick — part alarm, part battle plan — that across species helps the body fight invaders.

A not-so-brilliant medical history

People have tried hilariously questionable things to “fix” fevers. The ancient remedy list includes starvation, bloodletting and other medieval-grade DIY treatments. For a long time, folks thought the fever itself was the disease, not a symptom.

Everything changed after germ theory arrived in the 19th century. When scientists like Pasteur pointed out that tiny microbes cause infections, doctors stopped blaming fevers and started treating the actual invaders. No, washing your hands isn’t dramatic — it’s science.

What is a fever, anyway?

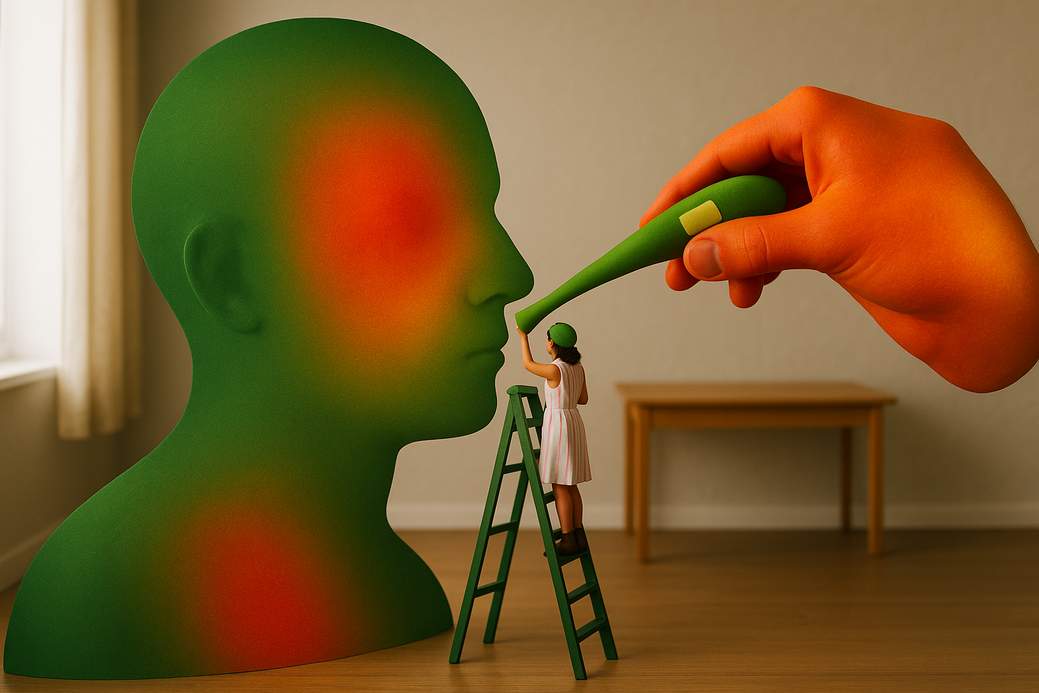

In plain terms, a fever is when your core temperature rises above about 38°C (100°F). That spike can be caused by infections, immune system hiccups, inflammatory conditions or even vaccines. Your body basically nudges the internal thermostat up because cooler temperatures are more comfortable for germs.

Think of it as a temporary factory reboot: enzymes and immune cells work a bit differently at a higher temperature, which can make your body a less hospitable place for bacteria or viruses. But like any good reboot, it should be short-lived — too cold is bad, too hot is worse.

Why fevers can actually help

Fever is part of inflammation — the full drama package that includes redness, swelling and loss of function. The heat helps immune cells sprint into action and can slow microbial growth. Animals across the board, from fish to lizards, raise their body temperature during infection (cold-blooded creatures just do it by sunbathing or moving to warmer water), which suggests this trick has paid off evolutionarily.

Fevers also change your behavior: you eat less, you rest more, and you generally behave like a sensible houseplant. That forced downtime gives your immune system a better shot at clearing the intruder.

When a fever flips from helpful to harmful

Not all fevers are benign. Mild, short-lived temperature bumps are often useful; prolonged or extremely high fevers can cause dehydration, organ stress, brain dysfunction and, in extreme cases, death. Temperatures above about 40°C (104°F) are especially risky if they stick around.

Kids can be extra dramatic with fevers because their temperature regulation isn’t fully tuned yet. Febrile seizures can occur — frightening, but usually not long-term harmful — so it’s important to seek medical advice if that happens. Also, a persistent high fever can be a red flag for serious infections like meningitis, pneumonia or sepsis, which need prompt treatment.

Should you try to bring a fever down?

Short answer: maybe. Fevers can help, so automatically suppressing every low-grade temperature spike isn’t always smart. Letting the body do its thing for 24–48 hours can be reasonable in some cases, provided the person is stable, well-hydrated and monitored.

There are caveats. Antipyretic drugs (like acetaminophen or ibuprofen) can make people feel better, but they might also encourage sick people to resume normal activities and spread infections more widely. And if someone’s very young, very old, pregnant, or has other health problems, it’s safer to check with a clinician before playing thermostat judge.

Bottom line

Fevers are annoying but often purposeful. They’re an old-school immune boost that helps make the body inhospitable to microbes and rallies your internal defenses. However, they can turn dangerous if they’re too high, persistent or accompanied by worrying symptoms. So sip fluids, rest, keep an eye on symptoms — and when in doubt, call a healthcare professional. Your immune system might be doing the work, but you don’t have to be a martyr to it.